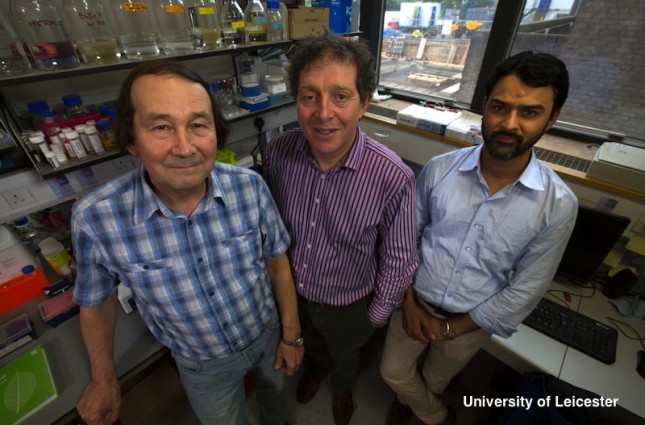

Scientists at the University of Leicester say they are a step closer to finding a cure for malaria.

According to the World Health Organisation malaria currently infects more than 200 million people worldwide and accounts for more than 500,000 deaths per year.

The researchers at the Medical Research Council’s (MRC) Toxicology Unit based at the University of Leicester and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine say they have discovered new ways in which the malaria parasite survives in the blood stream of its victims, a discovery that could pave the way to new treatments for the disease.

Malaria is caused by a parasite that enters the body through the bite of an infected mosquito. Once inside the body, parasites use a complex process to enter red blood cells and survive within them. By identifying one of the key proteins needed for the parasite to survive in the red blood cells the team have prevented the protein from working and thereby kill the parasite – in this way they have taken the first step in developing a new drug that could treat malaria.

Professor Andrew Tobin, co-lead author of the study said: “This is a real breakthrough in our understanding of how malaria survives in the blood stream and invades red blood cells. We’ve revealed a process that allows this to happen and if it can be targeted by drugs we could see something that stops malaria in its tracks without causing toxic side-effects.”

The study which has been funded by the Medical Research Council (MRC) and the Welcome Trust – use state-of–the-art methods to dissect the biochemical pathways involved in keeping the malaria parasite alive. This included an approach called chemical genetics where synthetic chemicals are used in combination with introducing genetic changes to the DNA of the parasite.

The researchers found that one protein kinase plays a central role in various pathways that allow the parasite to survive in the blood. Understanding the pathways the parasite uses means that future drugs could be precisely designed to kill the parasite but with limited toxicity, making them safe enough to be used by children and pregnant women.

Co-lead author, Professor David Baker from the London School of Hygiene; Tropical Medicine, said: “It is a great advantage in drug discovery research if you know the identity of the molecular target of a particular drug and the consequences of blocking its function. It helps in designing the most effective combination treatments and also helps to avoid drug resistance which is a major problem in the control of malaria worldwide.”

Professor Patrick Maxwell, chair of the MRC’s Molecular and Cellular Medicine Board, said: “Tackling malaria is a global challenge, with the parasite continually working to find ways to survive our drug treatments. By combining a number of techniques to piece together how the malaria parasite survives, this study opens the door on potential new treatments that could find and exploit the disease’s weak spots but with limited side-effects for patients.”

Most deaths occur among children living in Africa where a child dies every minute of malaria and the disease accounts for approximately 20% of all childhood deaths.